Transhemispheric Fieldnotes

14.-20.6.2019

Puerto Rico

CAA joined a research field trip to Puerto Rico on the invitation of Luis Berríos-Negrón and hosted by Michy Marxuach, Fernando Lloveras, La Esquina Residency and Para La Naturaleza, in June 2019. Fieldnotes by Taru Elfving:

The field trip felt simultaneously brief and profound, as it formed a promising foundation for navigating the currents past and present that flow between the futures of the Caribbean and the Baltic. At the time of the visit, there were an increasing number of reports on how the temperature difference between the Arctic and the Atlantic waters is changing due to the warming of the Arctic accelerating, and consequently, how the streams connecting the continents in the Northern Hemisphere are weakening. Weather has turned weird, winds appear out of sync, rain no longer knows other than extreme tempos.

As the climate breaks down, local phenomena cannot be meaningfully comprehended without an accompanying planetary perspective on the complex interdependent transformations. Meanwhile the global scale makes no sense without an acute awareness of what may seem at times like minute shifts in highly specific niches of ecosystems. Following our local guides along the various waterways on the island of Puerto Rico, uncanny resonances could be felt with the remote shores of the Baltic Sea and its thousands of tiny isles. Cautiously following an underground river in the labyrinthine cave system woven through the limestone Karso region reminded vividly of how geological time lays the ground for other temporalities – of fresh water, endemic flora and fauna, yet also resource extraction and industrial development.

The urgent necessity to protect waterways, the arteries of ecosystems, emerged as a reoccurring narrative for me during the trip. In the midst of the urban sprawl of the capital San Juan, a historical aqueduct is the sole place where it is still possible to access the river that is the life line of the city. Most seem utterly unaware today of these hidden natural infrastructures, the foundations of everyday existence. Privatisation and pollution alike may only be possible in these shadows of public acknowledgement, out of sight. This calls for sustained efforts to map and to make visible that which may still be conserved, as well as all those toxic leaks spreading and sedimenting due to rogue mining and manufacturing processes in the Nordic as much as the Caribbean region.

Like in so many places around the globe, it is only now transpiring that clean fresh water may not be taken for granted. Hurricanes, which have been since times immemorial the reoccurring powerful regenerators of Puerto Rican ecosystems, are now intensifying unpredictable: a year’s worth of rain in twelve hours, followed by up to five metres of water covering an old sugar plantation for three days. In the Nordic region, the winter snow fall is fluctuating dramatically from year to year, while this spring brought the second consequent year of drought in many places. How can the radically decreased biodiversity of the Finnish forests turned into timber plantations adapt fast enough? How much may have the ancient mangrove forests, if still intact along the shoreline, lessened the impact of the latest hurricanes?

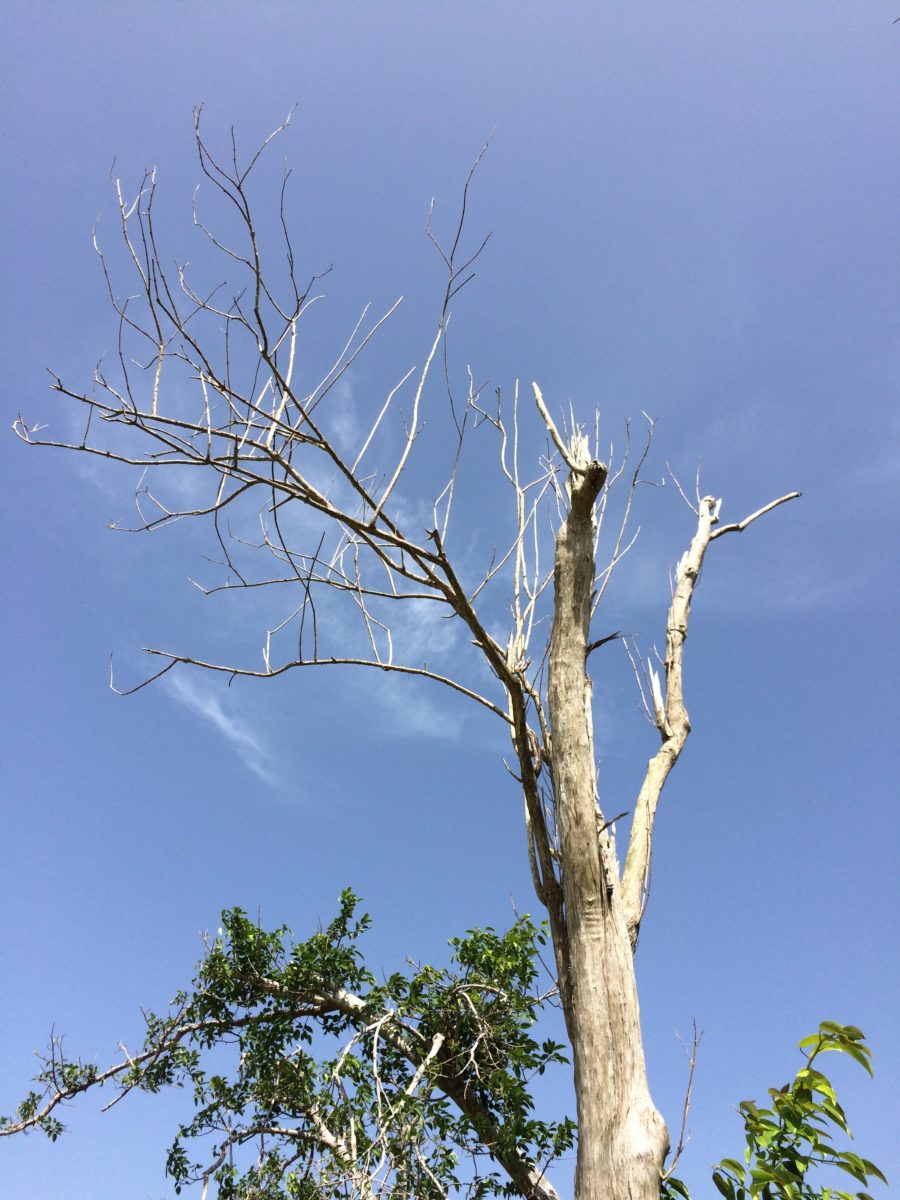

The hurricane damage is still visible in the Puerto Rican woods, where the ghosts of dead tree tops haunt the landscape. Lush shades of green are speeding upwards now, and the birds and insects have returned. Trying to imagine the eerie silence following the hurricane, I think of the sonic desert of vast clear-cut forests, where these days even the tree roots are unearthed together with all the ground covering plants, such as wild blueberries. This is called responsible forest management. Evergreens such as pines are planted to replace the now decimated ecosystems with monoculture rows of homogeneous aged woods here in the North. In Puerto Rico, however, nearly all the forest is already secondary, following the extensive plantations of the colonial times powered by slave labour.

One of the infamous old sugar plantations is now home to a tree nursery, where baby palm trees and other species endemic to the island are grown, soon to be planted amidst the 750 000 trees as part of an ambitious reforestation project. The history of the site is a stark reminder of the violence of slavery. Exploitation of natural resources and humans alike, across the world, formed the very foundation for the wealth accumulated from the colonies that Europe and the US continue to thrive on. In Puerto Rico, the natural and colonial histories are tangibly interlaced in the present. This draws into sharp focus the integral connections between environmental and social justice – not only here, but everywhere.

Islands are sites of intensified encounters and ceaseless flux, perhaps more than many landlocked places. This archipelagic interdependency goes hand in hand with highly specialised and precarious local ecosystems. Yet there is no return to some imagined original state of purity and balance, as Puerto Rico attests to with its history of ongoing transformations. Flows between islands and continents, of enslaved people, conquerors, and trade, of ocean currents and the winds, changing seasons and patterns of migration. The waves have brought with them both purposefully introduced foreign species of flora and fauna, and those that have unintentionally hitched a ride. Some invade and cause extinctions, some merely survive, while others are wiped out by this hurricane or the next one. Entangled fates across micro and macro scales.

Addressing the question that haunted my visit – of how to “go visiting”, politely and with care – is the next step in the development of what will hopefully become a slowly unfolding and long-term transhemispheric dialogue. The field research was yet further proof of the irreducible value of local expertise across a range of disciplines and vernacular fields of knowledge. Faced with the incapacity to read signs in an unfamiliar ecosystem, or to even recognise a sign there in the first place, it is necessary to humbly acknowledge the limitations of one’s own tools of navigation and understanding. Yet thought may indeed only happen in and as the event of encounter, rather than that of recognition.

How to nurture these transformative encounters and the potential of thinking with and across differences, and around shared concerns? How to take time to shift our practices accordingly, so as not to reproduce colonial modes of exploitation or presumed access to places and to knowledges? How not to fall back to reductive polarisations, idealisations or assimilations in desperate search for hope in the dark? How to be attentive to the spectres haunting every place as well as the shadows one’s own methodologies cast, while also insisting on the right to opacity when needed? How to not be carried away by the surging wave of emergency, when slow and small steps also matter in the face of the dawning complexity of it all?

The visit was part of the development phase of Transhemispheric Residency Program for artists and researchers focused on climate crisis and related environmental urgencies. It was funded by Nordic Culture Point and Nordic Cultural Foundation.