Interview with multidisciplinary artist Kati Roover

In connection with her ongoing research on the islands of Seili and Nauvo, multidisciplinary artist Kati Roover speaks with Selina Oakes at CAA about her approach to environmental changes and challenges through poetic imagination. Her practice, which spans across the mediums of moving image, sound, photography, text and installations, draws upon and addresses a broad range of topics – from human-non-human interactions, decoloniality, mythical storytelling, feminist new materialisms and maternalisms, to the natural sciences and ecology. Roover has become increasingly interested in spending time with the archipelago to foster a deeper connection with its flora and fauna, and to perform a gratitude and protection ritual with the surrounding environment.

Roover’s film The Scent of the Changing Sea will be screened on Saturday 3rd September, 2022, at Kino Diana, Turku, as part of the Exercises in Attentiveness event. Pre-book here.

CAA: What inspires and drives your practice?

Kati Roover: There are certain themes that repeat in my work: hydrofeminism and the politics of care, caring, slow movement, dialogical aesthetics, postcolonial thinking, plants and relationship with the non-human, mythical thinking, indigenous philosophies and practices are all interwoven in my practice. I have always been interested in the roots of big scale changes in human cultures, and recently, after becoming a mother two years ago, I have become more attentive towards environmental activism and the maternal. María Puig de la Bellacasa’s book, Matters of Care, has played an important role in my research, together with texts by Adrienne Rich, Silvia Federici, Astrida Neimanis and Andrea O’Reilly. I am interested in how intergenerational traumas affect mothers, their relationship to their own body and mind, and their ability to take care of others – be they human, more-than-human or the environment. Often, mothers are the primary caretakers and set the first example for children on how we live with the environment and with others.

In western-society, the mothering story has been one of survival, without external support, for many generations. Also, there is a lack of understanding of matrescence, the process of becoming a mother – a term coined by Dana Raphael in 1973 to describe the developmental passage where a woman transitions through pre-conception, pregnancy and birth, surrogacy or adoption, to the postnatal period and beyond. The exact length of matrescence is individual, recurs with each child, and may arguably last a lifetime. The scope of the changes encompass multiple domains – bio-psycho-social-political-spiritual – and can be likened to the developmental push of adolescence. How can we solve these enormous problems we have if we are left alone surviving when we have new human life in our hands? I hope that we, as humans, soon realise the necessity of living in more nurturing and trauma-sensitive societies.

I am learning how we can support each other, mourn the loss of species, and practice life-supporting traditions. Everything in life is constantly shapeshifting and many cultures have understood the importance of celebrating transitions and transformations.

CAA: What are you currently working on?

KR: I am currently working on multiple projects, and continuing to work with sound, video, images, text and the poetics of place. Thematically, I am focusing on the imaginary gap between the human body and other watery bodies, as well as nonlinear time and cyclical happenings. Later this year, I will release the sound piece H2O – Creatures. It has been a process of looking at the vast cultural changes in which water’s cyclical time has been condensed into the modern-day element, ‘H2O.’

Today, the mythical stories of water have disappeared in the midst of a linear time defined by man. Human bodies, and the efficient processes created by them, work as modifiers of water to structure its flows in the environment: water has become a commercially available and manageable material. However, water remains a permeable channel, a cyclical cycle of time, and an all-embracing sensor – capacities, which by their very nature, register change and challenge the senses to experience a different reality.

I am also working on Viriditas, a two part audio-visual project consisting of a book and video-sound piece about plant-human relationship, consciousness and overcoming the ‘plant blindness’ that human cultures have created. Recently, I have started a project about maternal thinking, acts of care, matrescence and how all of this is important for the future and survival of the human species. It is still in its very early stages.

CAA: How has working in Seili contributed to your artistic work and research?

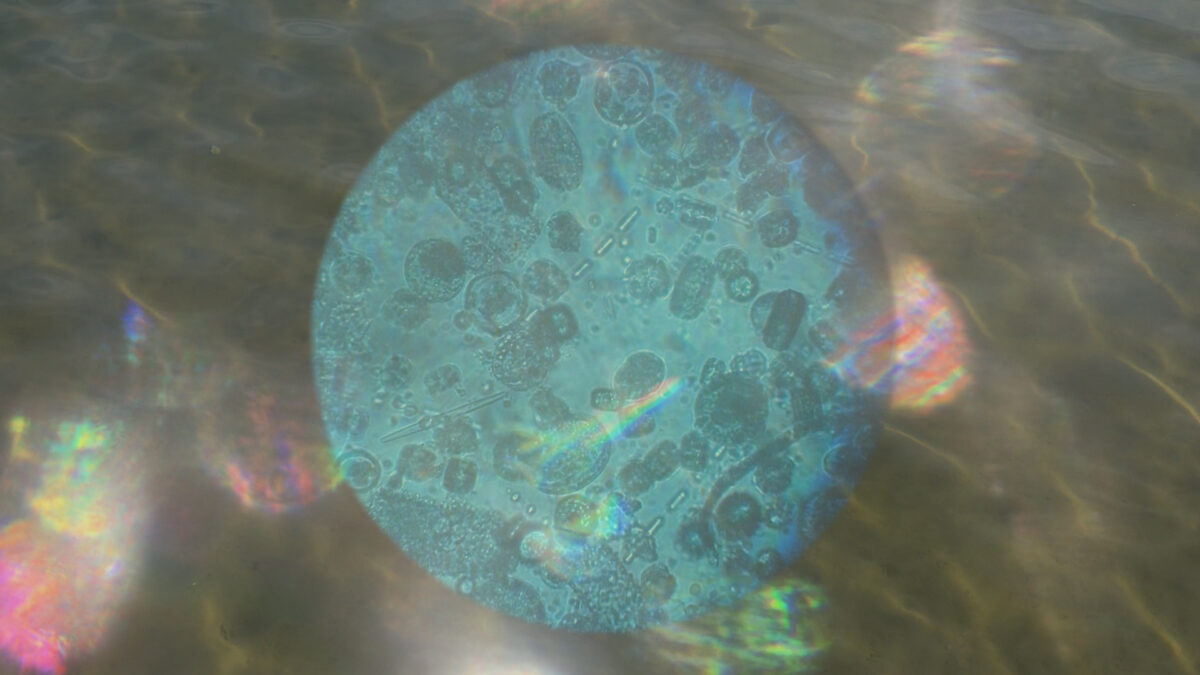

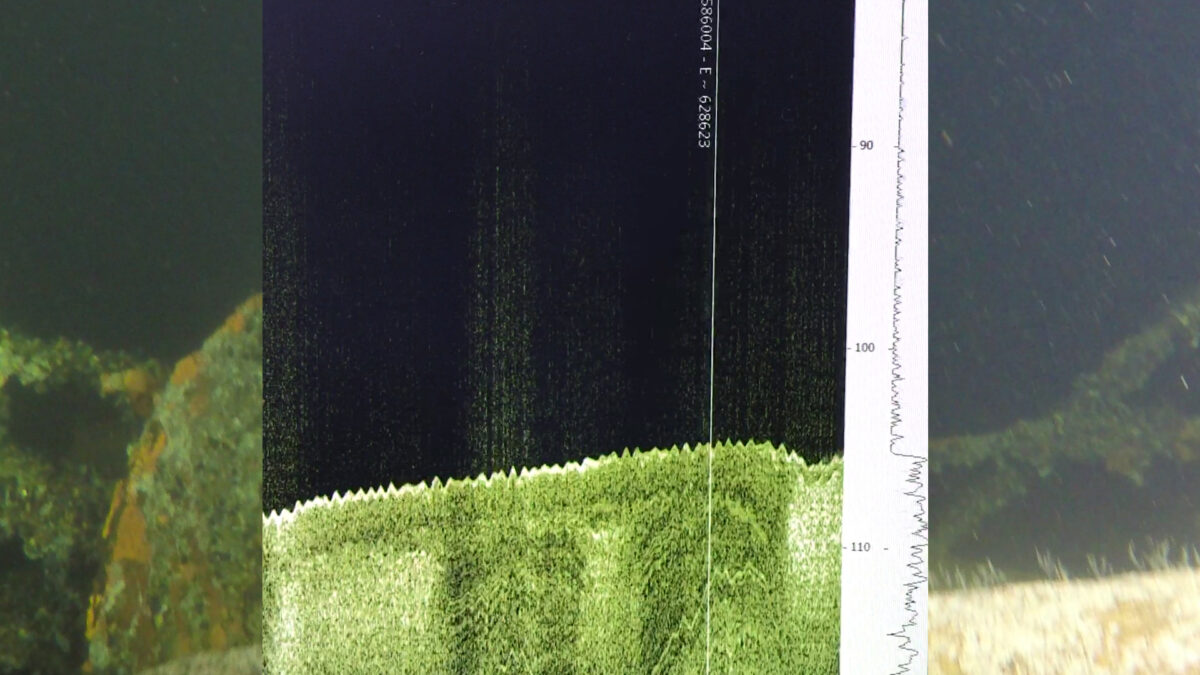

KR: Working in Seili has been important for my artistic practice. Coming back to the same place in different seasons, having discussions with Taru Elfving and Lotta Petronella, meeting with other artists and scientists working with and in Seili has been very fruitful for me. There are so many precious moments intertwined with the island. One place can have so many layers and connections to the outer world. Meeting Ilppo Vuorinen at the Archipelago Research Institute and learning from him was deeply inspiring and helped me to understand the Baltic Sea through deep time, distant pasts and futures. The Baltic Sea is a shapeshifter and in my work I speculate what kind of future it will have. I am very thankful for this opportunity to learn about Seili and the sea around it.

CAA: Could you talk a little about your commission, The Scent of the Changing Sea, and how the piece stimulates alternative avenues of thought?

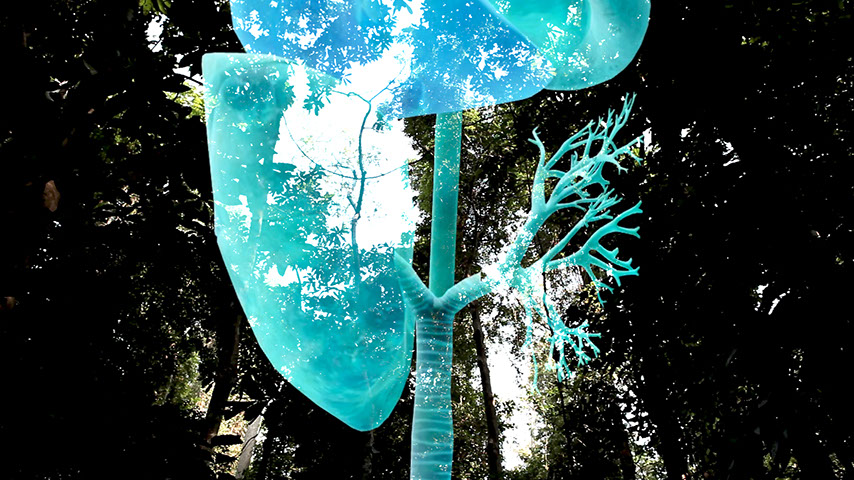

KR: The Scent of the Changing Sea, a video essay and installation, started when I was invited to make an artwork for the Finnish Environment Institute about underwater sound pollution in the Baltic Sea. I collected a lot of material from their archives, alongside filming underwater videos and documenting sounds. Later, I continued with the project in Seili and began to think about how the smell of salt water will disappear – there are already places in the Baltic Sea where it smells like fresh water. The video essay weaves together multisensory experiential knowledge and scientific observations in a poetic reflection on the distant past and possible futures of the Baltic Sea. I will continue working with the Scent of the Changing Sea, re-editing and combining it with new video footage collected in Seili this summer. I am also making an iteration of the work as a written and still image essay for a forthcoming (2023) hydrofeminist publication edited by Elina Suoyrjö and Anastasia Khodyreva.

I am now trying to seek out knowledge located in between linear and circular thinking, and to bring those stories into my video and sound piece. I plan to incorporate more narratives of travelling into the future, as well as back into the past to a time when the first human cultures were settling on the Finnish islands. I am interested in the presence of human-made labyrinths called ‘Jatulintarha’ on islands in Europe. It is known that fishermen went through the labyrinth before entering the sea and it was also used as a place for birthing and fertility rites. It encourages nonlinear thinking and opens us up to the unknown. Right now we are at a point in history where we need tools to navigate through an unknown and unstable future.

Rocks and mosses can also encourage us to consider the ‘long view’ when it comes to timescales. Mosses, for example, are like time made visible; they create a kind of botanical forgetting in which the past is embodied within greenery. In Robin Wall Kimmerer’s words: “That’s why we have stories, so we can remember. The mosses remember that this is not the first time the glaciers have melted. If time is a line, as western thinking presumes, we might think this is a unique moment for which we have to devise a solution that enables the line to continue. If time is a circle, as the indigenous worldview presumes, the knowledge we need is already within the circle; we just have to remember it to find it again and let it teach us.”

CAA: You have been devising a gratitude and protection ritual on the islands of Seili and Nauvo. Could you say a little more about the ritual and the significance of performing it on/with these islands?

KR: The ritual takes place in two parts: the first component, realised earlier this year, included a walk through the Jatulintarha labyrinth in Nauvo; the second part will feature a journey to Seili to perform a ritual inspired by prior consultations with two shamanic practitioners. The plan is to visit Seili in late autumn with a focus on letting go and giving thanks to the island. I have chosen to perform the ritual on Seili because it is a place that has many layers of troubled human history on a microscale – and it has an uncertain future ahead. It will be my way of closing the circle; to thank the island and the sea for its gifts. I usually perform some kind of gratefulness gesture after finishing my artworks.

The idea of performing a ritual, particularly on Seili, came from the history of violence in mental hospitals. The culture we are now living in has been divided into mind and body. We are still living in an age of reason in which the spontaneous trance experience has been pathologised. Those who move easily into trance states are often diagnosed as mentally ill. However, trance is something that has been used in healing rituals, and many traditions employ it as a generative tool. Hence, trance could be perceived as endemic to the human condition. My interest in innate traditions that make healthy human culture has led me into this gesture of ritual.

CAA: What is important about trance states in the 21st century, and what might a renewed understanding of them facilitate?

KR: Trance conditions include all the different states of mind, emotions, moods and daydreams that human beings experience. All activities which engage a human involve the filtering of information coming into sense modalities, and this influences brain functioning and consciousness. In following this logic, trance could be understood as a way for the mind to change the way it filters information in order to provide more efficient use of the mind’s resources. Trauma itself is a very trance-like experience; a state of being in the past and in the present at the same time. I have learned that Seili has been a place for those who are, in some ways, traumatised.

Right now, we are going into a collective trance state faster than ever before, because we are following fake news and conspiracy theories, scrolling our phones and being in many places at the same time. I can see how we need bodily trance experiences, permeated with intention and concentration, more than ever. We need to learn how to experience trance in safe ways, because trance also has its dark sides: for example, both the military and politics use trance-inducing propaganda, repetition and fear as fuel for violence. Moreover, trance can be a very addictive experience.

Nevertheless, being in a place, fully present and in a trance-like flow, may be a way of accessing the unconscious mind for the purposes of relaxation, healing, intuition and inspiration.