Interview with artist duo Matterlurgy

Matterlurgy (Helena Hunter and Mark Peter Wright) have been working with the island of Seili since spring 2019. The London-based duo first travelled to Turku and its archipelago as part of the Spectres of Landings retreat; this visit was followed by a research residency on the island in autumn 2021. The duo are set to return to Seili for an in-depth practice and methods exchange with scientists, while also participating in the How do you know what you know? Exercises in Attentiveness event on 12th August.

Within their collaborative practice, the artists investigate the critical ecologies of environmental change across disciplines and media, combining the production of artworks with co-constructed events, exhibitions and live performances. Selina Oakes catches up with Matterlurgy to converse about the impact that their discourse with Seili has had on their practice and projects, and to ask about their shifting perspectives on art-science collaborations and matters of water.

What have you been working on recently?

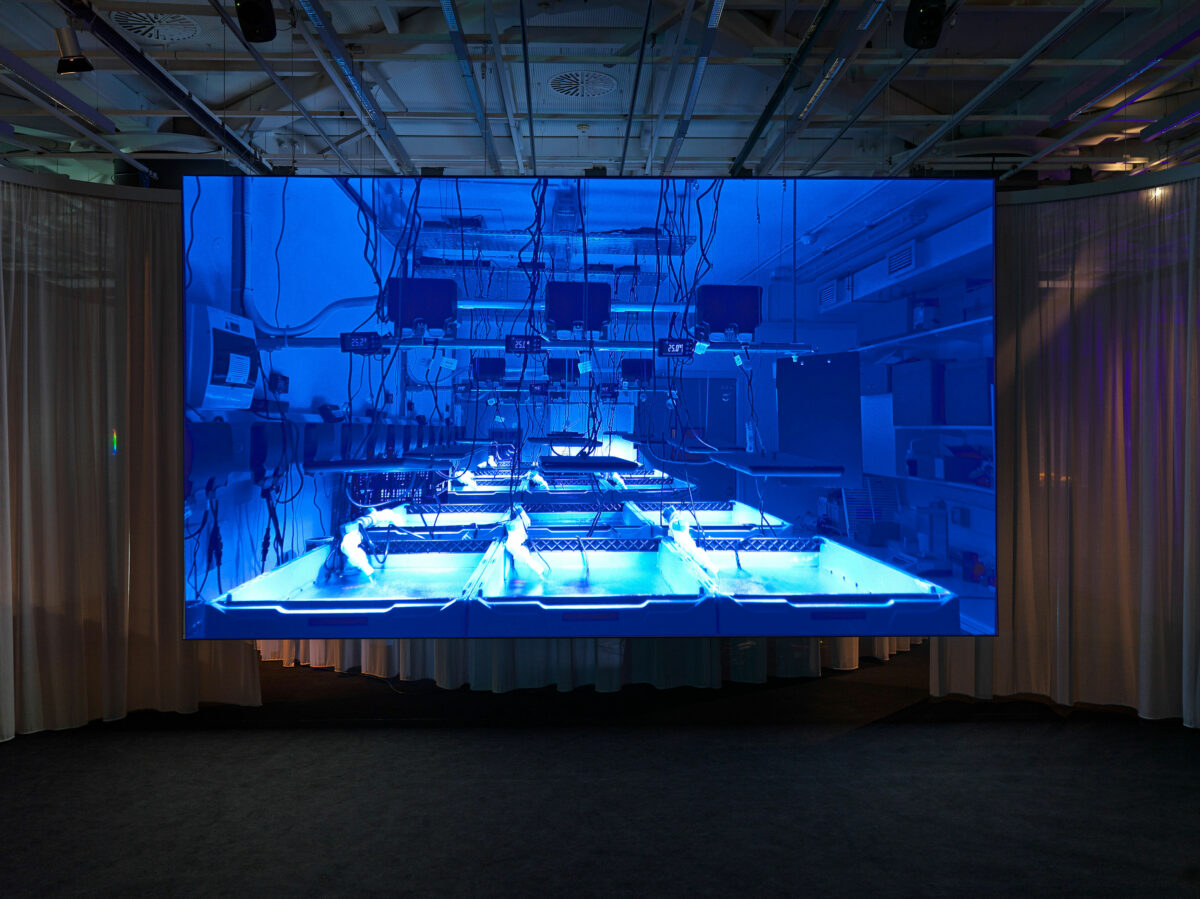

Matterlurgy: We have been working on artworks for a project called Weather Engines initiated by Daphne Dragona and Jussi Parikka. The commissioned works – Hydromancy, a short artist film, and Data Dialogues, an image and text work – were recently part of the Weather Engines exhibition at Onassis Stegi in Athens (1 April-15 May, 2022). Both pieces, made during a residency at the National Oceanography Centre in the UK, explore the spaces and technologies involved in ocean sensing and modelling. During the residency, we worked with oceanographers who collect and process data about the ocean. We were keen to explore the question of how data becomes data, and how we might dialogue with the invisible hand of its construction? We are interested in how the ocean is imagined within the field of science, so we wanted to examine the infrastructures behind data visualisations, and what goes into making them.

In much of our work, we’re interested in the people, practices and labour involved in producing climate data: this is an area that we have been developing in Seili, where we have had the opportunity to work with Professor Ilppo Vuorinen – a scientist involved in long-term monitoring of the Baltic Sea for 40 years. During our residencies on the island, we have been able to conduct fieldwork with Ilppo, like sampling and observing seawater in the lab. The first time we looked through a microscope at what we thought was essentially a drop of water, we got quite a surprise. There were so many tiny organisms of all different shapes and sizes, travelling at varying speeds.

The microscopic scale of these organisms and ocean plants belies their broader connection to the Earth’s systems. For example, phytoplankton are responsible for the oxygenation of the Earth’s atmosphere 2.35 million years ago; today, they absorb more CO2 than forests and contribute considerably to the production of the world’s oxygen. Ilppo is an expert in phytoplankton, zooplankton and copepods. The level of detail in which he notices their different features is astounding. But the years spent looking through microscopes has affected his shoulder. We’re interested in the tacit knowledge and physical registers that are accrued through science in practice. We’ve been discussing with Ilppo about the relationship between fieldwork – sampling phytoplankton with a net out on the open ocean – and automated data collection. Our conversations have pivoted around what is gained and what is lost with each method. From these discussions, we have been considering if the body of the marine biologist is in the process of becoming ghostly or spectral in the move towards data and automation.

How has working in Seili contributed to your practice?

M: Seeing how lively water is through the microscope in Seili was incredibly influential for us, and has contributed to the development of our work and practice considerably. Following our residency in Seili, we began to work on a project about river ecologies that asked a very simple question: what is in the water? To try and answer this question, we collaborated with river ecologists Professor Lorraine Maltby and Professor Philip Warren from the University of Sheffield. This research, part of Arts Catalyst’s Test Site programme, was located in Yorkshire’s Calder Valley. We quickly learnt that what is in, or absent from, the water is incredibly important to river ecologists in terms of deciphering water quality. For example, an abundance of sludge worms can be a sign of phosphates in the water, whereas lots of caddisflies can indicate good water quality. The research we did with Phil and Lorraine led to a vibrant online digital artwork, Sensitives Stream, that blends film, poetics, science, participatory scores, podcasts and a series of workshops with Whitechapel Gallery and Arts Catalyst. We’ve continued to explore these interests in our recent works Hydromancy and Data Dialogues, and we’ll be pursuing this further on Seili through a project called Field Casting.

How do art and science converse in your work?

M: This, in some respects, is dependent on the project, the context and ideas that we are investigating. Nevertheless, within our projects – over time and through our collaborations with scientists working with environmental data – we have accrued methods, knowledge and experience. One of the key aspects of our collaborative work is to practically share and exchange methods, tools and technologies across art and science. This does not happen immediately and sharing in this way is built up through trust and developing a framework of care and understanding across the different practices that we are working with. For example, in our work on Sensitives Stream and our collaboration with river ecologists, we engaged in fieldwork with them, using nets and sensors to do sampling, collecting and analysing organisms in the water. There was a lot of conversation and exchange, of sharing information and data, to understand how scientists work with water organisms as indicators of pollution and the nuances and complexities of this research.

Within this project, the scientists also got to ‘try out’ our own field-based methods. We ran listening sessions with the river using a range of microphones to hear the river’s different sonic elements. We also facilitated a series of critical poetic sessions, where we shared writing methods engaging with the river and exchanging findings through the composition of collaborative poems. These methods really brought out the differing and complementary aspects of noticing and engaging with the river across art and science. Over time, this work is distilled into what you experience in the online digital artwork. An important element of our engagement with scientists is the way in which we are transparent about the way we work. From the onset, we communicate about our practice and discuss the ways in which we endeavour, not to simply illustrate or communicate science, but to enter into a form of critical relation.

In asking ‘what is in the water?’ you have been able to engage with water as more than an abstracted commodity or material. How have your activities shifted your everyday perceptions of water, and how might these changes impact your return-visit to Seili?

M: In Seili, we encountered the microscopic world of plants and organisms; water became alive in ways that we had not previously encountered. When we saw the hundreds of organisms existing in one droplet, a shift in how we engaged with ‘it’ occurred. ‘It’ was no longer an ‘it’ but more a plural scene. When we had finished working in the lab, we carefully returned the water to the sea, feeling slightly awkward and ethically compromised about removing the organisms from their habitat.

This sense that water is a ‘habitat’ and has a delicately balanced ecology was further developed during Sensitives Stream. For example, we learnt how the leaf matter that falls into rivers becomes a form of sustenance for river organisms. If trees along the river banks are cut down, these organisms struggle to survive and this can have a dramatic effect on the entire food web. On one of our walks with Phil, we talked about present-day industry, increasing housing and agriculture, and how these activities impact water: we started to understand that the river is not really a river but a composition of the land. Its chemical composition is informed by the human and non-human activities that act upon it.

We will be returning to the idea of ‘reading’ water through its organisms when we next visit Seili in August. We have been conversing with Professor Marjut Rajasilta and Postdoctoral Researcher Katja Mäkinen at the Archipelago Research Institute in Seili about their practice of reading data and information in the ear bone, or otolith, of the Baltic Herring – a fish whose changing physiology has been linked to climate change and the shifting conditions of the Baltic Sea. This summer, we will visit the Archipelago Research Institute’s otolith archive and learn more about Marjut and Katja’s research. We are interested in the non-human knowledge and experience that accrue in the otolith which becomes a kind of archive, a black box of sorts, that scientists read, speculate and draw climate predictions from.