‘I..sland,’ we land, it lends

Field notes by researcher Anastasia Khodyreva following the retreat Spectres of Reason I on the island of Seili, 14-17 September 2021:

~

‘I..sland,’ we land, it lends.

Written with Seili, an ‘i..sland’ I walked-with for the third time.

Onomatopoeia is a process of creating words that phonetically imitate, resemble, or suggest sounds. They are the sonic enfleshments of the bodies and matters they describe. Put another way, onomatopoeia is a world-making process. Words world worlds. Would attuning to an ‘island’ mean one might hear how its wor(l)d was made? How did they listen? Who listened to Seili and its kin across the world, to these lithic bodies – rocky lumps of aggregated minerals, so that they became ‘i..slands’?

Meeting me while I am still adrift, the ‘i..sland’ first asks for a brief inhale. A grasp of air … enough to roll the lithic body of Seili around my mouth. It rolls with a gesture of limbs and saliva which rhyme with the waters I am brought by. These are the waters which – on a calmer day – gently pet Seili’s shoreline. Further, Seili allows one to step on its rocky land. That is, ‘i..sland’ ends with a thud of a foot encountering its moraine body. I land and touch upon Seili and it touches me back. A string of thuds dots our walk. We come together – in a mutually transformative encounter, step-p–p step-p–p step-p–p.

Take a deeper breath if you wish to walk an ‘i..sland.’ Inhale the “i..” letting the winds that greet us who stand on board of a ferry reach you, pierce you. The winds deliver slight goosebumps. They are chilly. Let their chills brush your tonsils and “land” with a firm but slightly murmurous “d.” An “s” of an ‘i..sland’ is quiet but not silenced. It is a curl and froth of the wave which washed the ferry towards the ‘i..sland.’ It echoes all the waves which ever brought ships to Seili. It is their sibling.

You have now made an “i..sland,” with us who are about to make it for ourselves. …

‘I..sland’ is an English word, the language we all speak in our group and the language which defined an island as an isolated crumble of land big enough to settle. It is bigger than ‘islets’ that might only be teasing with a possibility of (settlers’) step-p-ps. Islets are mighty enough to refuse mapping, appropriating, extracting human feet.

The ‘i..sland’ echoes the steps of the Western colonisers who walked out the world as a patchwork of ‘lands’ surrounded by waters. Waters were viewed as mere passive gaps, an abyss of nothingness separating one lump of resources from another: plantations from mines, forests from sites of oil and gas extraction. How do we step with Seili? Do we step better than that?

…

Taking us around her Seili, Lotta (Lotta Petronella, an artist, filmmaker, herb whisperer, chef, and Contemporary Art Archipelago’s soul) reminds us that islands are chains of mountains resting down in the murky blue-ness of the Baltic sea. For many that is a moment of estrangement for, as terrestrial creatures, we may imagine islands as isolated entities. But even if ‘i..sland’ was a floating body detached from the Earth’s core … would it be isolated? Where does any body – lithic, humanly fleshy, marine or of a herring – start and where does it end? As Donna Haraway considers the consequences of thinking skin as an end of a distinct human body (Haraway 1990, 220), I wonder why a body of an ‘i..sland’ need end at its rocky contour?

…

Seili’s anthropo-imagined isolation has been commodified and appropriated in many ways. Its sedimented histories include a designation as a leper colony or, rather, exile, and a containment facility for mentally divergent women and other unruly souls.

Currently, the Archipelago Research Institute takes Seili’s samples, classifies everything what the ‘i..sland’ is: herbs, herrings, algae, ticks, temporalities to come and histories which are currents. The Institute practices containment but in order to tackle residues of colonialism, coloniality and environmental crisis. It observes herrings adapting (or not) to the Baltic Sea salinity. It observes so as to know how to care. How can we learn – with and from the Research Institute and with the ‘i..sland’ – to sample, catalogue and classify ethically, that is, to sample, catalogue and classify towards more sensitive ethics of relatings to the ‘i..sland’?

Lotta shares with us a story of Leila Linnaluoto’s herbarium. Following the photographs gently radiating from the screen of Lotta’s computer, I meet Seili’s plants bending and at times bowing to fit on the page. Their bodily stretch, their adjustments are supported by tiny tidy strips of white paper and glue. They are supported by the touch of someone’s hands that once glued and named, that left us small stories of each plant when marked its precise location on Seili. The photographs weigh so much more now when I think about the labour in materialising the herbarium. I imagine not only the handwork, but someone’s limbs and knees bending to reach a plant, feet muddied by Seili’s swampy patches if that’s where a sought plant resided, a palm scratched by the ‘i..sland’ if a plant enjoyed higher rocky shelters.

Not meeting the requirements of a proper scientific catalogue, that is, simultaneously telling too little and too much, the herbarium is an unruly abject in Seili’s archive. It landed in Lotta’s dissident, carrying, and observant hands, which seek to acknowledge the labour and the materialities which co-compose it, hands which notice and value stories differently to standardised scientific protocols. How may we learn to acknowledge – with Lotta and the herbarium – that sampling, cataloguing, classifying might yet become acts of care and story-telling radically alternate and disobedient to acts of extraction and appropriation? How to catalogue in a way that would care about relations with and relatings to the “i..slands” and all the minerals and species of which they are?

…

///

We walk with the “i..sland” and it gently but resolutely asks us to attune to its haptic encounter with the glacier, a quasi-terrestrial body that ragged Seili’s flesh thousands of years ago. The glacier can easily be forgotten by our selves that have mainly been trained to observe and notice linearities and process with heads and brains. Our little group is critical of purely embrained ways of knowing and wanders around unlearning to follow existing paths. Humanly linear, coherent and quick temporalities begin to crumble when we encounter Seili arching its lithic back in front of us, when it makes us face its curves, wrinkles and cracks.

Invested in knowing with ice, glaciers, processes of melting and thawing and politics they might be hinting, I walk with the group and attempt to nurture sensitivities that would smell, hear, attune to the glacier which is not to be seen but present in all the meaningful twists of Seili’s metamorphosis and of its slower neighbour bodies: islets and the sea.

Acknowledging the glacier we learn to be in meaningful touch with bodies slower than our own. We speculate towards the futurities of reciprocal but specifically multispecies and transcorporeal care. The glacier’s visual absence is the beginning of our listening towards careful reciprocity (Voegelin 2010, 83).

…

There is some comfort in stepping upon Seili’s rocky skeleton, but the mosses make me feel as if I am stepping on the island’s creaturely belly, its guts.

With Kati (Kati Roover, artist and fellow hydroreader), we walk and wonder why a soft surface causes a stepping foot to feel hesitant about incipient encounters? Elina (Elina Suoyrjö, curator, writer, and co-creator of Aquatic Encounters: Arts and Hydrofeminisms) makes me slow down and think of feathers, another soft but yet again life-enabling matter for the swan family she notices when walking with the ‘i..sland.’ What soft gimmicks could we think of that might radically shake our dominant Western ways of relating to lands, islands, mosses, rocks as objects?

~

We t/walk about time.

A few of us stop where the sea used to ripple, in-between Seili and an “i..sland” where now dwell the church and the cemetery with suspiciously few crosses, if one considers how many lives these rocks harboured, but also took away. Taru (Taru Elfving, writer, researcher, curator, and CAA’s rock who refuses to ‘be taken for granite’) notes that if one stands attentively here, one can feel the geological time – in wetness of the land, in curves of the landscape. The muddy patch we stand on has risen over the years, for the rocks have been and are still bouncing, looking for a fulcrum since the glacier left.

Here, one can hear the ‘i..sland’ whisper to us with its already icy September winds: it whispers that it should not be ‘taken for granite,’ a nod towards Ursula Le Guin’s refusal to stand still and pretend to be sealed and solid, her determination to stay in a muddy flux of her body, in constant metamorphosis (Le Guin 2004, 8-9).

Following the glacial touch, we are now approaching Seili’s rocky forest. I walk the last. When the hillside unearths too rough in its angle, I feel my body leaning towards the rock. My chest wishes it had some fingery if not tentacular possibilities to secure this ascent or, in Michel Serres’s wording, to have “maximal hold on the world” (Serres (1999) 2011, 4).

Seili’s curves do not scratch me. Rather, they are sure to hit if my boots slip. Suddenly, they transform my hesitant leaning into a momentary climb.

As a climbing body, I am pushed into a state of visceral and cutaneous alertness of how my nascent body is of a nascent space emergent relationally with a lithic curved, mossy, and moist body of Seili. Alert of my momentary climb, Seili infinitesimally crumbles. Crumbling, it enhances my haptic knowing that, while scratching my palms, the rock, in fact, supports me. My body radiates with sensibilities, apprehending each of its organs as fingery, assessing incipient possibilities of my next grab that would let me safely relate to Seili. The curve which one might have imagined as a lump of solid immovable matter became my companion, generous and warm, but not resolutely kind. It slips from under my boots but continuously offers additional possibilities, promising grabs. It only offers, ambivalently.

Seili is quietly and gently cracking its reputation of a solid unaffectable self. It now unearths, in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s term, in its enduring vivacity , unnoticed by those humans who observe out of haptic sync with earthly spatialities (Cohen 2015:6-18). I am now in touch with this vivacity. We are of each other and of touch, “a material embodied relation that holds worlds together” (Bellacasa 2017, 115).

Following Serres, a moving body that walks, hikes, climbs, is a body perpetually involved in learning, as while moving it crosses a space full of messages (Serres [1985] 2019, 141). This is a body that unlearns its certainties and volition to feel a life-defining togetherness with other bodies which are human and non-human, organic and inorganic. It grabs and opens itself to be grabbed in order to survive or, in my case, not to slip. How may I re-member, that is, sensorially reconsider in a meaningful way what my body is capable of enacting? How to re-member with a climb, and, if needed, to slip better, to slip ethically, to slip well?

~

Seili is a body which is of the glacier, of crystallised elemental unions which rested here centuries before the icy river of time, matter and possibilities slid through and pierced them, of mosses, of climates, of sea salinity and currents which pet and hit – all mingling in a multiplicity of “nonexploitative forms of togetherness” (Bellacasa 2017, 24) from which we must learn to step-p–p, to be together, the forms which should not be lazily imagined before they happen.

Is the slippery Seili hinting that one must learn to sensorially re-scale minutes of a climb or a daily walk with little pebbles jumping from under one’s boots … as centuries-long durations of lithic transformations? Is Seili hinting that what is to crumble is an image of the worldly as passive immobile matter, a spatial container awaiting inhabitation, the imaginary instrument for the ongoing project of colonialism and coloniality? Is the glacier still hinting for us, walking with Seili, that one must sense and touch (even if senses and touch evoke unease) in order to care-fully notice residues of other durations which co-compose the ‘i..sland’ but any of futurities we might live?

Appropriation, extraction, erasure, emptiness before arrival. All must crumble. How to stay in touch with Seili? How to touch better? How to touch more ethically? How to touch well?

~~~

Finally, hiking the curve of Seili together, I stand mesmerised by the view. The view is of mingling, crossing, knotting and rippling lines of shore and waves, but also the scratches of abrasion quietly radiating where the ‘i..sland’ touched me. All lines are liminal, all in flux.

I cover my ears with my chilled, abraised palms and hear … the ocean. A rock is a body of water held as dovetailed hydrogen and oxygen in the atomic structures of aggravated minerals co-composing Seili. It is also a body of water washing its shores. The ocean could not be heard here unless tides, temperatures, curves and cracks were in meaningful touch … to generate its aural body. Here, the ‘i..sland’ refuses to speak English, it speaks oceanic, lithic, mutually constitutive, inseparable, and slow.

What may an island – imagined as a body of water – tell us? How may it guide us towards more liveable – aqueous – futurities in the rapidly liquifying world?

…

///

Up slippery curves tangled by pines, Seili reminds those of us who are still speaking English up here that it only lends. I am an ‘i..sland,’ and “I lend.”

To lend is to give something to someone for a limited period of time with an expectation that this something will be given back. To lend is to grant temporarily. What does the island lend? And how could one give back to the island which lends? Aren’t we always already late because it lives slower than we do? Who and what are these ‘we’ that are to give back? How to re-turn that which has been lended? How to know how to re-turn and what exactly am I to re-turn?

How to know?

How do I know?

How do I know that I know?

Do I truly need to know in order to give back?

As it did several years ago and yet again two months ago, Seili lends its milieu for my sleep. I know that I will not sleep here on my first night. I’ll be listening, not sleeping because I will not be able identify the island’s murmurations.

I am alert and awake. The unknowing-ness first gives me discomfort.

But the next day, it will transform into cherished un/certainty, friendly enough to envelop me in a light dormancy. The body will know the sounds but will not explain them to me. And it should not. I do not need to know, that is, identify, categorise, catalogue, or classifixate in ways I tend to do when on the mainland. I need to trust that my body knows. And it does and it is relating ethically, it is relating well.

By my second night, I lend my ear to Seili – full-bodiedly – and fall asleep.

There is no going back to that first step of Seili’s guest. What I want to do is pay multisensorial haptic attention to how I step now and may yet be stepping again. Instead of focusing my gaze and relying on paths and maps, I shall disperse my attention. I shall dis-embrain it in order to step better. I shall dis-embrain to keep learning – full-bodiedly present with Seili – how to step well.

Glossary of gestures:

… – little rocks of the island

/ / / – cracks of rocks and the lines on the map which show where the glacier lacerated Earth for islands to appear

~ – time, always approximate and incoherent

~~~ – water is time, incoherent, approximate

Acknowledgements:

I thank Taru Elfving and Lotta Petronella for yet another encounter with Seili and for an opportunity to word the ‘i..sland’ as I felt it. I thank Elina Suoyrjö for making Aquatic Encounters: Arts and Hydrofeminisms happen, for sharing its invigorating space & time and for reading- and thinking-with all that waters can be. I thank Ayesha Hameed, Saara Hannula, Audrey Samson & Francisco Gallardo, Kati Roover, Johannes Vartola and Inna, Ilppo Vuorinen, Marjut Rajasilta and, of course, the island of Seili.

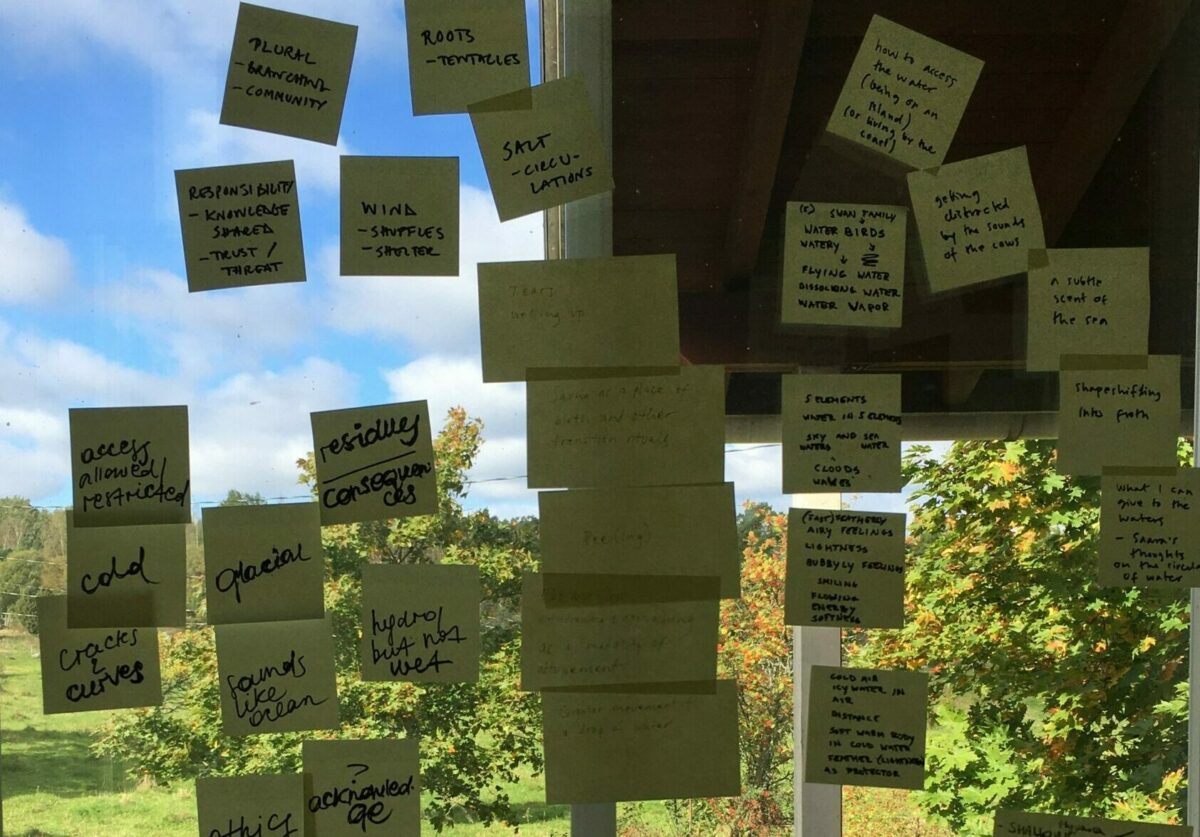

The post-its that accompany the text are a part of a group sensorial exercise co-facilitated by Elina Suoyrjö and myself.

I wholeheartedly thank Rowan Lear for taking care of the text’s flow of commas, slashes, and full stops.

References:

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds, 2017.

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. Stone. An Ecology of the Inhuman, 2015.

Ursula K. Le Guin. “Being Taken for Granite.” In The Wave In The Mind. Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination, 2004.

Donna Haraway. “A cyborg manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the 1980s.” In Feminism/Postmodernism, ed. Linda Nicholson, 1990.

Michel Serres. The Five Senses: The Philosophy of Mingled Bodies, [1985] 2019.

Salomé Voegelin. Listening to Noise and Silence. Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art, 2010.