Anja Örn

Red Herring Fieldnotes

Fieldnotes and Reflections I

The island perspective becomes clear quickly – already when the trip is booked, one must respect the sea, that is a fact. Gotland is somewhat difficult to reach, and the times must be adjusted according to how we enter the island. As soon as we are there, together, it unites us: the sea and the islands, the actual conditions.

My body feels a sense of relief and my brain can rest in the outer geographical limitations. Now, this is where we are. Pause.

Then we meet around a table, and everything is generous and well thought out. Time to get to know each other and the room we are in. I hesitate a little, feeling somewhat unprepared. I let the feelings settle and trust the situation.

Tomorrow’s plans are drawn up and it is easy to find my way home to the hotel.

The research station and the researcher

We ride together across the island, to the north. It is beautiful in autumn, and there is a lot of talk in the car. Arriving at the Ar Research Station, we are met by Gunilla Rosenqvist, who will accompany us the next day as well. Gunilla shows us around and tells us about the project, ReCod, which is now, metaphorically, dry and wrapped in plastic foil. The small cods have moved to another, more suitable place, and it feels empty there in the experimental hall. Some kind of sadness stays in the room, a loss from the buzz that once filled it: instruments, water, fishes, and researchers. And now, nothing.

We learn about the Baltic Sea’s temperatures and salinity, and how these factors affect the cod’s opportunities for reproduction and development. We also learn why the cod population is important for the Baltic Sea, and catch glimpses of details of the ecosystem to which the ocean belongs.

Presentations of each other’s locations and activities then follow, and in Mara’s and my case, our artistic practices. Our gaze becomes clear about who we are, what the places and islands are, and what the direction of this project can be. I like that the different kinds of places and organisations bear various experiences – it is a good prerequisite for curiosity.

Mara shows works that deal with circulation and flows. She mixes and filters, and remixes. Closed systems are translated into beautiful landscapes of slowly moving liquids. I think of bodies, blood systems, and lungs, as well as the delta landscape of a river. Maybe Mara is visualising how fluids always choose and create their paths in the same way, according to the same pattern. She has documented how the liquids slowly find their way into large vessels made of transparent plastic – drop bags for artistic experiments.

I talk about my project In memory of a river and show the film that is part of the work. We travel between rivers, hydro power plants, and historiography; we touch memories, maps, and power.

The room provides good conversation and there is so much I want to talk about and tell. I can’t quite finish, nor can I rank all the stuff I want to try to vent right here. I am thinking that it might be good to share, but there is just not enough time.

A walk

We also take a short walk in the rain, out on the stone field and down to the sea. It smells like the sea, but doesn’t taste that salty. Almost like home, where the sea is pushed aside by the river.

As we unpack the car, I think about the rooms, the research station – a place for conversations and meetings, for investigations and curious eyes. There was also a workshop. Most things should be possible here.

The sea

We brave the rainstorm and continue out into the gray. Stop briefly at Fårö, marvel. Raincoats rustle, the sea roars. Everything gets wet – the face, the legs, the hands. Here I am almost nothing, just a small wet dot. Like washing your head of everything, making room for new thoughts.

The bird painter

The next day we go south, into another landscape. The conversations continue, as if without a break. Now we are going to visit the bird painter, he who has painted birds his whole life, Lars Jonsson. After an introduction to Naturrum, we are invited to coffee and a presentation of Lars’ artistry. Later, when we are shown around the exhibition, he tells us about his childhood, how he sat in the trees and wanted to be a bird. How he tried to see and mimic their facial expressions, their looks. Imagine starting your artistship and life there, in the desire for a transformation.

Once outside in the well-planned garden, I thought that he, the birdpainter, had offered us the opportunity to zoom out of ourselves for a while and take a break from all the thoughts and ideas that spin.

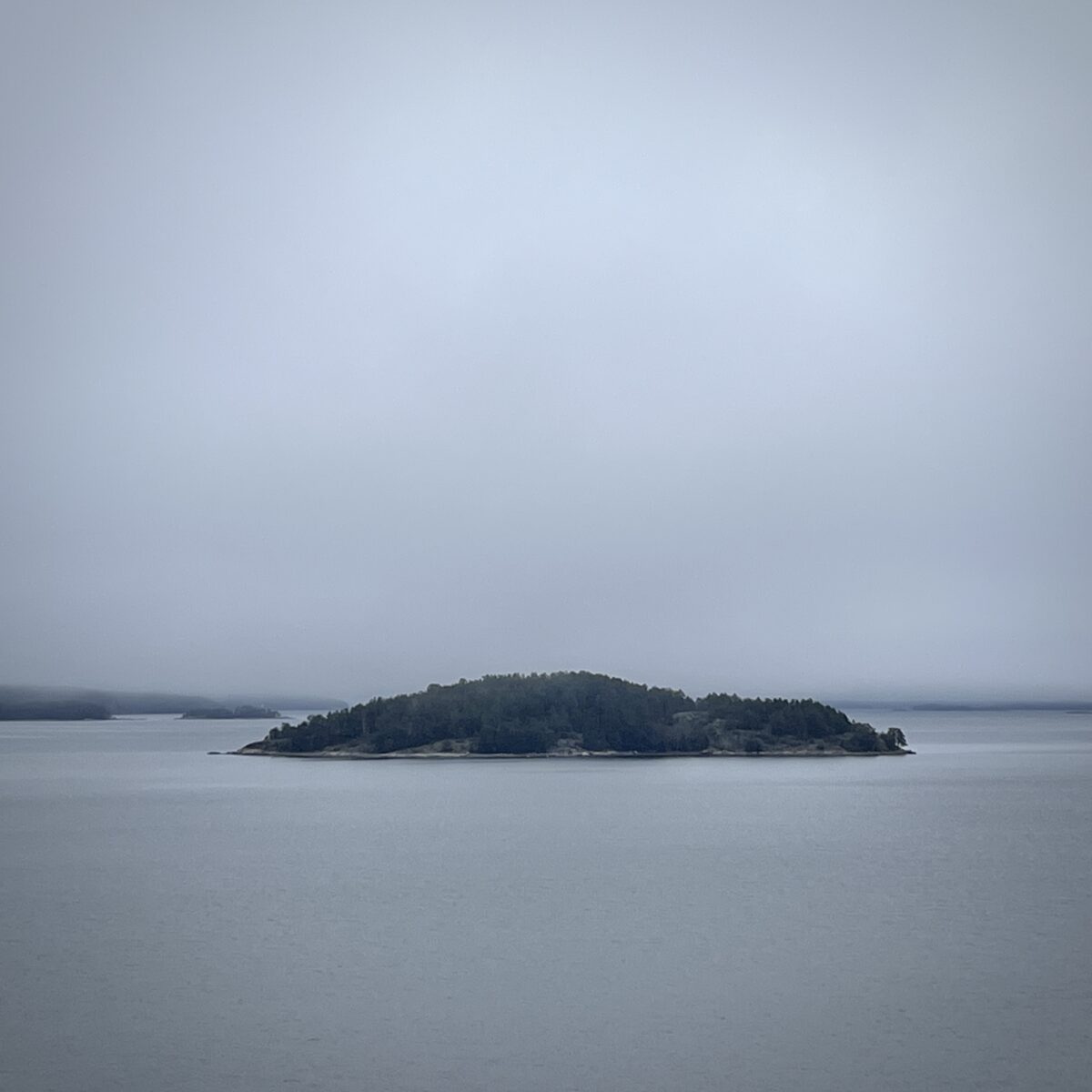

The sea

Back in the car, we follow the coast; the fog and debris come and go. Stora Karlsö and Lilla Karlsö appear for a short moment before disappearing again. Reminisce for a while. Stora Karlsö is a longing place, I want to go there again. Reflecting on the almost ridiculousness of being able to relate to a place, or as in this case, a guise, a gray shadow out at sea. But I know it a little, and it has some kind of meaning. The water tastes slightly more salty here.

The researcher

Back in Visby, we get to meet Beatrice Krooks at the University of Gotland. She talks about how, in her research, she analyses strontium isotopes in the teeth of fish, and how it is possible to read out times and places in the Baltic Sea via salt levels that leave traces in these isotopes. A complicated mapping, which seems to be able to expose fresh water supplies and movement patterns from different layers over time. Trying to understand we are looking at small brown details from animal skeletons. I have to sit down. I don’t like rooms with so many dead individuals in them – so many bags and boxes filled with small skeleton parts. Beatrice is passionate about her subject, and inspires more knowledge.

The summary

In conclusion, we talk about the project onwards, how it could take shape and develop. In addition to the practical matter of who should meet who and where next time, we are thinking about future deepening.

I’m finding it hard to pull myself together after today’s two study visits. Everything wants its own presence and now it’s a bit hard to find Red Herring again. Zoom in, zoom out.

I return to yesterday and the research station in contemplation. And together with today’s study visit, it becomes clear that I want to get to know the water.

I don’t know exactly how, but I become curious about the water’s own body – its density, how it moves, and how it reflects its surrounding environments.

Turn the map over and start from the water that surrounds us.

Ar Research Station – is it possible to start from that house and the good feeling of curiosity and benevolence that sort of impregnates the place? A research station and a residency are mutually intelligible, a good place for cross-genre collaborations and thoughts.

With me back in Luleå, I also carry a growing curiosity about the national park, which will be next to the research station or surrounding it. It is a super special situation that is happening right now. Since in my own practice I end up at the points where different interests meet and squeal against each other, I have also noticed that ecological and cultural interests do not often seem to have an interest in consensus. Hierarchies between the fields of knowledge have become visible to me. When a national park is formed, I become curious about what different considerations are taken, and how that knowledge is created or found. I am also curious about how natural and non-natural changes in the park are reasoned. And also about memories – if a national park can be seen as a preservation of memory, and if so how. Is it possible to create memory structures in such a place?

Among dislodged thoughts found in my notebook is the sentence: art’s ability to find itself in a problem and stay there. To turn and twist it, without presenting a solution. A strength and necessity for deep knowledge, I think.

And then there’s the value of friendships for creativity and knowledge production.

Fieldnotes and Reflections II

The journey itself between Luleå and Seili also describes these places. It’s a kind of presentation where time, space, and forms of transport provide information about their position, surrounding settlements, and landscapes. One gets small clues to social structures and orders.

How we met up in Turku and then continued together towards the island was a nice and warm start to the days to come.

Seili is a fantastic little island. I experienced how everything is concentrated when limits are set by the smallness of geography. The steps shrink and I become aware of the details.

There are many layers of history on Seili to take part in. The immediate past, with its marine research and art projects, and the more historical past, with its hospital first for leprosy patients and then for the mentally unwell.

The research is in the same building as the history. It’s nice that a museum site houses the future and its researchers. They are part of the building and have been doing their work there for a long time. I feel that research and museums are sometimes linked via the art projects on the island. Projects that also sometimes connect nature with the contents of the main building in different ways. It’s inspiring.

Like little prophets, badgers hide under the foundations of the building, while paths are formed around their perennial dwellings. This activity takes place under the same wing that the researchers also work, the wing that faces the forest. Agreements have been made to work in different shifts during the day. They look cosy as they wander out at dusk and provide a kind of homeliness that only animals can create.

We spend our days walking and talking. Our small group reorganises itself along the paths and during breaks. It’s nice to walk and talk in the beauty, to learn from the others about the island, the flora, the water, its activities.

Everything is a walk, and all walks are one or more conversations. We talk between the house where we sleep and the one we cook and eat in. We talk on the way to the research station, the museum, the sauna. We talk when we cook and when we wash the dishes. We talk when we eat.

I think it must be the method of the small island to let conversations move like the surrounding water, in the movement of the waves, back and forth over large and small topics and landscapes.

Various presentations give us insight into the research at the station and into each other’s artistic practices or activities. It’s all about the water, the salt, and the herring. About living conditions in our sea. About how our waters, and specifically the Baltic Sea, are being harmed by human activities, emissions, and climate change. They are changing and in need of help. The presentations are also about our practices, and different approaches to water in our artistic processes.

The question of what we contribute from the art side circles around us, though not directly stated. In the global great hope to stop the negative human impact on the environment, I always carry with me the question of what task could be mine. I think we all do. Around the table and on our walks, we touch on the topic. The question itself is far too big, and it helps to break it down in time and space. To delineate it. The island has a good shape for standing still in the details—it is possible to be in the here and now and only sparingly step back to widen your gaze.

Our travels have helped me realise that the water itself is something I want to devote more attention to. I have long worked beside the water, looking at the consequences of hydropower, lost memories in a restructured landscape, hierarchies of power, and around the extraction of natural resources.

But now I must turn to water itself. It is one of the most important components on the planet, giving birth to life in the form of plants, animals, and oxygen. It has a capacity to carry and not to carry. To give power and to destroy. One must understand a water, and be gentle by its side.

Water has material properties, yet in some ways, it does not. It interests me to understand what water is. Besides being a chemical compound of oxygen and hydrogen, water also has a body just as it is also a movement. I’m curious about that, and whether I can define that body and movement into a material. I want to shift my gaze and start from the perspective of water, not from my own view nor any other’s. That’s where I stand now.

I take the idea of the body and movement of water home with me. And when I look at ‘my water’ – the sea in the far north, where one of several mighty rivers flows out – I think, almost childishly, that perhaps our sea has a direction? Can an ocean have a given flow, a starting point? I have probably thought of rivers as running water, lakes as bowls, and oceans as large containers vaguely connected to each other, where water masses mysteriously move around the Earth. Now I couldn’t help but wonder if the sea might have an even clearer movement, a given direction?

What if the Baltic Sea has a primary starting point, a beginning, and that beginning is up here in the north, where the great rivers flow into the sea? What if the sea ‘starts’ here in the Gulf of Bothnia? If the Gulf of Bothnia were to be seen as the starting point of the Baltic Sea, it would make great demands on us. Eyes would be turned northwards and it would be necessary for the rivers to become healthy again. They would be allowed to rest and to be restored. Their waters must be filled with life and movement. We would protect them from the threat of mining. We would look into hydropower and how much life it can be allowed to reduce. We would have to provide waters filled with life and oxygen.

It’s always good to turn things round. Trying things on their edges and upside down. If the Baltic Sea was said to start here in the north, then the north would be seen as a prerequisite for functioning important ecological systems. It’s a hopeful thought for a timeworn place in a troubled time.

About the artist:

Anja Örn is an artist and organiser who runs Galleri Syster in Luleå together with Sara Edström & Therese Engström. Örn is also part of Norrakollektivet (The North Collective) together with Tomas Örn and Fanny Carinasdotter. ratdragonproduction.se

Red Herring homepage