Mara Kirchberg

Red Herring Fieldnotes

A belly of water held in a plastic shell

While spending time on Gotland (Sweden) and Hiiumaa (Estonia), we visited two fish hatcheries that have stayed with me – both very different in scale, but similar in intention. One was ReCod, a cod restocking initiative at the research station in Ar; the other, a small, almost hidden hatchery project run by the local fisherman Imre Kivi in a secluded corner of Hiiumaa. These encounters became starting points for thinking about reproduction, care, and the conditions required for life to take hold – and to be sustained.

Fish lay their eggs externally, which means fertilisation happens in the water. In this way, the water body becomes an active part of the reproductive process – uterus-like yet something more open and shared. I think of it as a kind of belly: a holding space, an external organ of incubation that holds and nurtures developing life. Just as amniotic fluid supports human life in utero, the Baltic Sea requires very specific conditions for life to thrive.

Unlike internal reproduction, this process relies on environmental stability – temperature, salinity, and oxygen levels must remain within narrow bounds. Reproduction becomes a negotiation with the environment, exposing a mutual dependence between life forms and their surroundings. Extractive practices have left deep marks in the belly of the Baltic Sea. Common fish such as cod, herring, and sprat are increasingly threatened. The environment they depend on has become fragile and unstable.

To support the recovery of local cod populations, the lab at the research station in Ar, was filled with systems consisting of incubators, spawning tanks, and rearing environments – mimicking the natural environment of the Baltic Sea water in ideal conditions inside a plastic shell. This environment is designed to allow fish eggs to hatch and young fish to grow in the safest, most controlled conditions before being released into the Baltic Sea.

When we arrived, the ReCod project was in a transition phase – no fish eggs or larvae remained, just the equipment. Active at the station from 2020 to 2024, the project was preparing to relocate in 2025. What we encountered was an emptied infrastructure, its original inhabitants and purpose temporarily absent. Outside, much of the hatchery equipment had already been cut up and stacked for disposal: plastic tanks, pipes, hoses…

What struck me seeing these empty vessels was how plastic containers – made from petroleum, one of the very extractive forces damaging the sea – were now used as care infrastructure, as artificial organs keeping the sea’s metabolism going. It’s a paradox that continues to draw my attention.

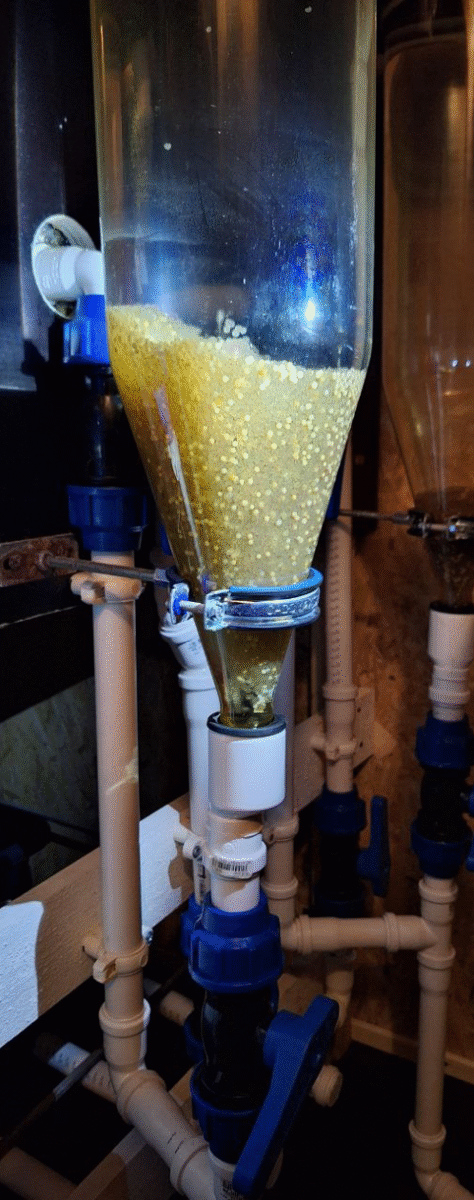

Imre’s small-scale hatchery on Hiiumaa shifted my focus. Outside, heavy snow is falling. We step into a small hut. At first, its placement seems random – just a modest structure in the open landscape – but it makes sense once we learn it’s positioned next to a freshwater spring. Inside, the light is low, mimicking the dimness of winter to prevent the fish eggs from hatching too early. The brightness will only increase with the arrival of spring. We peek into the three funnel incubators where thousands of eggs float gently in suspension. What is usually abstract – early developmental life – becomes tangible.

Imre tells us how he built the system himself – cobbling together parts, adjusting flows, checking temperature and oxygen levels by hand. His presence is quiet, methodical. Listening to him brings the whole process down to a human scale. The repetition, the close attention, the steady maintenance – it’s less about control than about staying with the process. It made the act of dedicating oneself to transformation – however slow or partial – feel more real. Not as a grand promise of change, but as a way of being: one that sharpens sensitivity, reorients attention, and holds space for other relationships between body, environment, and time. Maybe that’s what becomes more visible when the plastic shell that holds the belly is smaller: not the machinery of intervention, but a practice of living-with.

In my artistic practice, the human belly has often served as a starting point for exploring bodily functions, particularly in relation to metabolism, vulnerability, and interruption. I’m interested in how extractive systems leave traces, not only in ecological environments but also in bodies. I’ve come to think of the Baltic Sea as a kind of metabolic organ too: a fluid system where disruptions manifest not simply as environmental changes, but as symptoms – signals of deeper systemic imbalance. Like the body, the sea responds to stress, care, and neglect.

How to live with these symptoms? This precarious need for ongoing care is something I also return to in my work through sculptural processes that resist finality, and through performance-based maintenance routines that ask what it means to sustain rather than fix. A large part of my practice involves visiting car workshops and medical facilities to learn, exchange, and collect discarded equipment – fragments that have lost their original function. I see a parallel in the plastic tanks, pipes, and hoses piled up outside the research station in Ar: once part of a care infrastructure, now disassembled, waiting for a different kind of use or meaning.

I create hybrid systems – we could also call them artificial organs – from materials in which fluids circulate without the efficiency of motors and pumps, just by gravity and manual assistance. Much like the work being done to ‘restore’ the belly of the Baltic Sea, these systems rely on painstaking, slow, and labour-intensive gestures. Their effects are not immediate, but instead become visible through long-term processes of testing, study, failure, and partial success.

What matters most to me – in my own practice and in the hatchery projects I encountered and hope to continue engaging with – is the cultivation of a practice of care: a mode of working that values sensitivity, intimacy, and slowness, and that holds space for more-than-functional forms of connection. I imagine this line of thinking extending into a more speculative direction, where sculptural and textual work explore care infrastructures as life-support systems in uncertain futures, shaped as much by fiction as by ecological urgency.

About the artist:

Mara Kirchberg is a visual artist with a background in choreography and performance. Based in Berlin and Tallinn, Kirchberg’s work examines notions of efficiency and exhaustion, investigating how they shape bodily systems. The artist creates sculptural and installative scenes, as well as site-specific interventions, that open up anatomical and architectural interiors. With a Brutal tenderness, these works reveal the mechanisms that nourish the organs of living bodies, buildings, and machines. marakirchberg.com

Red Herring homepage